My Mumbai Mirror column:

Awtar Krishna Kaul's 27 Down, which won two National Awards in 1973,

remains a visually arresting reflection on India's train journeys

The

connection between films and trains dates back to cinema's origins. One of the

Lumiere brothers' first films was of a train arriving at the station in La

Ciotat, a small French town near Marseilles. Arrival of a Train, shot in

1895, is central to the mythology of the movies. The claim (made in several

film histories) is that early audiences leapt from their chairs in alarm as

Lumiere's locomotive seemed to race towards them. Even in soundless, jerky

black-and-white, the story goes, the power of the moving pictures was such that

people – almost -- couldn't tell them apart from life.

In recent times, film historians have cast doubt on this narrative, some pointing to

confusion with a later stereoscopic version that Louis Lumiere exhibited in 1934. But

what is indubitable

is that there was something endlessly watchable about this simplest, single

shot of a train. Trains had screen presence.

Both the railways and the cinema arrived in India soon after their

invention, swiftly becoming integral to our social and cultural life. So it's

no surprise that trains are a fixture in our films: The staging ground, as much for crime and

thrills as romance and recreation.

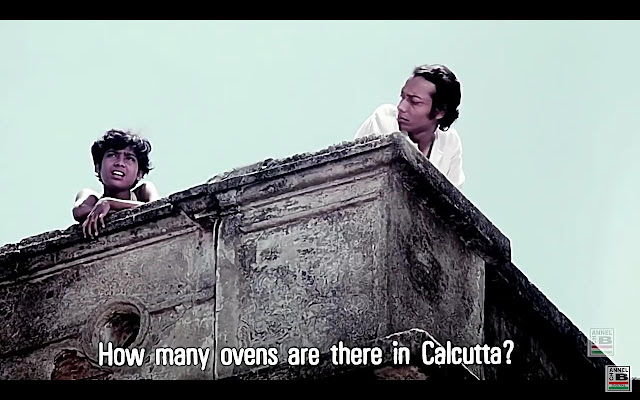

But perhaps the most devoted train film we've ever had is Awtar Krishna

Kaul's 1973 feature, 27 Down. Kaul, who had left his diplomat job to

study filmmaking in New York, returned to India in 1970 and became part of the

Indian New Wave: A spectrum of directors ranging from Basu Chatterjee to Mani

Kaul, beginning to make their mark in an era popularly defined by Bobby

and Yaadon Ki Baraat. 27 Down was Kaul's first feature, made

with the encouragement of Filmfare editor BK Karanjia, who

was then chairing the Film Finance Corporation.

Based on a Hindi novel called Atharah Sooraj Ke Paudhe, the

film stars a young MK Raina as the ticket-checker protagonist Sanjay, and Rakhee as his

girlfriend Shalini. Filmed in atmospheric black and white by cinematographer AK Bir (who had just graduated from FTII at the time and never

shot a film before), it won National Awards for Cinematography and Best Hindi

Feature -- days after Kaul died tragically in a drowning accident.

The film begins with the familiar drone of the Indian Railways announcer:

“Number Sattaaees Down platform number teen se jaane

ke liye taiyyar hai”, and is shot very substantially on trains and in stations.

Often assembling his shots to accompany a meditative monologue, Kaul's work

seems closer to the more experimental end of the New Wave. 27 Down starts

off ploddingly, in a self-consciously literary voice: “Phir koi pul hai kya?

Shaayad pul hi hai [Is it a bridge again? It's probably a bridge],”

Sanjay thinks to himself, lying supine on a berth as the train moves. “It feels

like I'm constantly crossing bridges...”. But there are playful moments, too.

The song Chhuk chhuk chhuk chalti rail, aao bachchon khelein khel adopts

the train's rhythm to create a visual and aural paean to it, with shots of the

locomotive moving through tunnels juxtaposed with children lining up to form a

train.

Son of an engine driver, Sanjay's life seems to keep circling back to

the railways. Born between two stations, as a child he is insatiably curious

about trains. He tries to study art in Bombay, but his father urges upon him

the stability of a railway ki naukri. As a ticket checker, Sanjay

discovers anew his

love of trains. He starts to eat and sleep on trains, even when not

on duty. Neighbours, landlords, even his father finds his peripatetic existence

strange. “Tumhare liye toh train hi ghar ho gayi hai,” his father writes

him.

It is on a train that he meets Shalini, who lives alone in a rented room

in Kurla and works in the Life Insurance Company of India. It is a railway

romance: She takes the train to work, he takes the train as work. When

his life plans are again forcibly aborted by his father, Sanjay surrenders himself

to the trains again – in metaphor and then in reality.

“I wanted a long path, instead I got these iron roads, where the

direction is already decided,” Sanjay muses sadly. A minute later he's grateful

for the effortlessness of the journey: “Chalti train hi sahara hai [The

moving train is my only support].” But then, there's the sense that he isn't

really getting anywhere. “Main guzar jaata hoon, aur jagah khadi reh jaati

hain [I move past, and

places stay where they are].”

Then he gets on a train to Banaras, looking to beguile himself with

women and wine, his beard getting scragglier. The sequence echoes so many

tragic Indian heroes, and yet it feels distinct. He looks at an old man on the

train, the old man looks intently back at him, and we imagine (wordlessly, like

Sanjay) that he is Shalini's long-lost father who may have become a sadhu in

Banaras. In a more conventional melodrama, Sanjay's echoing of Shalini's father's escape

from an unchosen domesticity would end in discovery, reunion. Here, it ends in a dream of death.

Perhaps what 27 Down's languid melancholy really captures is the

duality of the long-distance Indian train ride: You're in a crowd, yet alone;

relentlessly moving, but not of your own accord. And yet, the solidity and

predictability of India's trains makes them feel like something to believe in.

Get on a train, and the country seems to stretch out before you: Distant, but

somehow accessible. When Sanjay says, “Mera train aur bheed se

vishwas uthh gaya hai [I've lost my faith in crowds and trains]”, we know

it's over.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 4 Apr 2021.

Awtar Krishna Kaul’s 27 Down, which won two National Awards

Read more at:

https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/opinion/columnists/why-our-enduring-romance-with-the-railways-makes-for-great-cinema/articleshow/81893897.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst