My Mirror column:

The awkward event of a mature couple having a baby ends up offering an optimistic view of the Indian family inBadhaai Ho .

Since his debut inVicky Donor (2012), Ayushmann Khurrana has emerged as the Hindi film industry’s go-to actor for good-humoured family films about matters sexual. If Vicky Donor addressed anxieties around infertility and ‘naturalness’, Dum Laga ke Haisha (2015) and Shubh Mangal Saavdhan (2017) took on marital sex life complications: pre-judgement about female attractiveness in one instance, the man’s erectile dysfunction in the other. Badhaai Ho, too, belongs to this growing genre: taking the dark, shameful things we were only ever supposed to sob about solitarily and making us giggle about them collectively.

Director Amit Ravindernath Sharma, whose 2015 feature Tevar didn’t get credit for its attempt at creating a masculine small-town hero who respects women, creates another rather optimistic protagonist here. Khurrana plays Nakul Kaushik, the twenty-something son of fifty-something parents who finds himself profoundly embarrassed when his mother gets unexpectedly pregnant. “Tu hi bata yaar, yeh bhi koi mummy-papa ke karne ki cheez hai kya?” he demands frustratedly of his girlfriend Renee, mid-intimacy. The mental vision of his parents getting it on is enough to ensure that Nakul and his girlfriend don’t.

Nakul’s initial response is exactly what one might expect in a middle class Indian universe, where sex isn’t meant to exist except when given public ritual sanction by marriage, where it’s intended for the socially approved goal of procreation. Then, of course, the ‘success’ of a suhaag raat becomes the business of the whole family and community: think of both Dum Laga and Shubh Mangal.

But Badhaai Ho shows us how quickly even that socially legitimised conjugal bed can turn into something transgressive. A baby bump makes visible the existence of a sex life where we’d rather not imagine it: in our parents’ beds.

Badhaai Ho sets out to be winsome, and part of that winsomeness lies in the particular parents it presents us with. Jeetender Kaushik (the marvellous Gajraj Rao) is a Northern Railways ticket collector who’s miserly with his money and his mangoes, but remains warmly attached to his spouse Priyamvada (Neena Gupta ).

Priyamvada, for her part, supplements her domestic responsibilities with being the admiring audience for her husband’s amateur Hindi poetry written under the quasi-comic penname ‘Vyaakul’ (it is reading aloud his latest published poem that brings on a moment of passion). (Another recent portrayal of a middle-class couple, Love Per Square Foot on Netflix, had Supriya Pathak play an admiring wife to her railway announcer husband Raghuvir Yadav’s secret musical ambitions.)

The believable affection between the two is used to charming comic effect through the film — during the shadi song sequence ‘Sajan Bade Senti’, for instance, when Jeetender tries to get closer to Priyamvada within the space of a big family photo. Later, when he compliments her, she seems secretly pleased but tells him off because it’s his “saying this sort of thing that has put us in this mess”.

More interestingly, though, the film takes a very warm view of the joint family, where privacy and politeness might be missing, but bonds are strong enough to create acceptance, even in the face of declared social norms. It is clear where Sharma wants to go when he pits the Kaushiks’ cramped Lodhi Colony life against the cavernous bungalow inhabited by Renee’s single mother. There's a neat reversal of assumptions about social class and liberal openness: Sheeba Chaddha as Renee’s mother emerges as more judgemental —and less likeable — than Priyamvada.

From the fading mehendi to the sindoor in her broadened hair parting, Gupta makes Priyamvada layered and utterly real. Priyamvada is not a character one would call feisty, but there is a clear line between what she takes as her duties — e.g. listening to her mother-in-law (Surekha Sikri) — and what she takes as her due, e.g. the right not to have an abortion. There is also a way in which the film extends her maternal role from the familiar mode of asking after physical well-being (“Khana khaya tune?”) to inquiring, gently but firmly, after her children’s emotional health. The mother who can teach her son when to apologise in a relationship is a truly significant mentor in a world where so many men seem to grow up ill-equipped for emotional labour.

Badhaai Ho appears on our screens in a time when the opposition to court-approved entry of women into the Sabarimala Temple has brought women’s menstruating bodies onto our front pages. Given that powerful women like Smriti Irani still see fit to body-shame their own gender for a perfectly natural biological function, Neena Gupta’s smiling, quiet defence of her character’s ageing, but still sexual, pregnant body seems particularly valuable.

The family, Badhaai Ho implies, can be a space of socialising for young men, a place to learn what female experience is like, through empathy with sisters and mothers and grandmothers, through simple things like learning that periods happen, or how to hold a baby. Its vision of joint family may be rose-tinted, but in these divided times it is a pleasure to watch proximity create acceptance, not its opposite.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 30 Oct 2018.

The awkward event of a mature couple having a baby ends up offering an optimistic view of the Indian family in

Since his debut in

Director Amit Ravindernath Sharma, whose 2015 feature Tevar didn’t get credit for its attempt at creating a masculine small-town hero who respects women, creates another rather optimistic protagonist here. Khurrana plays Nakul Kaushik, the twenty-something son of fifty-something parents who finds himself profoundly embarrassed when his mother gets unexpectedly pregnant. “Tu hi bata yaar, yeh bhi koi mummy-papa ke karne ki cheez hai kya?” he demands frustratedly of his girlfriend Renee, mid-intimacy. The mental vision of his parents getting it on is enough to ensure that Nakul and his girlfriend don’t.

Nakul’s initial response is exactly what one might expect in a middle class Indian universe, where sex isn’t meant to exist except when given public ritual sanction by marriage, where it’s intended for the socially approved goal of procreation. Then, of course, the ‘success’ of a suhaag raat becomes the business of the whole family and community: think of both Dum Laga and Shubh Mangal.

But Badhaai Ho shows us how quickly even that socially legitimised conjugal bed can turn into something transgressive. A baby bump makes visible the existence of a sex life where we’d rather not imagine it: in our parents’ beds.

Badhaai Ho sets out to be winsome, and part of that winsomeness lies in the particular parents it presents us with. Jeetender Kaushik (the marvellous Gajraj Rao) is a Northern Railways ticket collector who’s miserly with his money and his mangoes, but remains warmly attached to his spouse Priyamvada (

Priyamvada, for her part, supplements her domestic responsibilities with being the admiring audience for her husband’s amateur Hindi poetry written under the quasi-comic penname ‘Vyaakul’ (it is reading aloud his latest published poem that brings on a moment of passion). (Another recent portrayal of a middle-class couple, Love Per Square Foot on Netflix, had Supriya Pathak play an admiring wife to her railway announcer husband Raghuvir Yadav’s secret musical ambitions.)

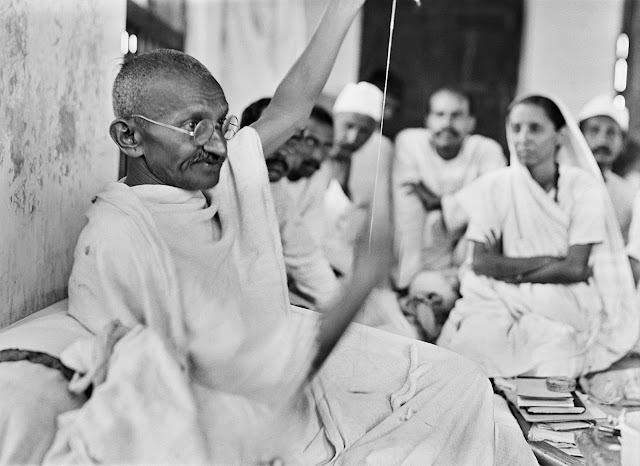

Ayushmann Khurana in a still from Badhaai Ho

The believable affection between the two is used to charming comic effect through the film — during the shadi song sequence ‘Sajan Bade Senti’, for instance, when Jeetender tries to get closer to Priyamvada within the space of a big family photo. Later, when he compliments her, she seems secretly pleased but tells him off because it’s his “saying this sort of thing that has put us in this mess”.

More interestingly, though, the film takes a very warm view of the joint family, where privacy and politeness might be missing, but bonds are strong enough to create acceptance, even in the face of declared social norms. It is clear where Sharma wants to go when he pits the Kaushiks’ cramped Lodhi Colony life against the cavernous bungalow inhabited by Renee’s single mother. There's a neat reversal of assumptions about social class and liberal openness: Sheeba Chaddha as Renee’s mother emerges as more judgemental —and less likeable — than Priyamvada.

From the fading mehendi to the sindoor in her broadened hair parting, Gupta makes Priyamvada layered and utterly real. Priyamvada is not a character one would call feisty, but there is a clear line between what she takes as her duties — e.g. listening to her mother-in-law (Surekha Sikri) — and what she takes as her due, e.g. the right not to have an abortion. There is also a way in which the film extends her maternal role from the familiar mode of asking after physical well-being (“Khana khaya tune?”) to inquiring, gently but firmly, after her children’s emotional health. The mother who can teach her son when to apologise in a relationship is a truly significant mentor in a world where so many men seem to grow up ill-equipped for emotional labour.

Badhaai Ho appears on our screens in a time when the opposition to court-approved entry of women into the Sabarimala Temple has brought women’s menstruating bodies onto our front pages. Given that powerful women like Smriti Irani still see fit to body-shame their own gender for a perfectly natural biological function, Neena Gupta’s smiling, quiet defence of her character’s ageing, but still sexual, pregnant body seems particularly valuable.

The family, Badhaai Ho implies, can be a space of socialising for young men, a place to learn what female experience is like, through empathy with sisters and mothers and grandmothers, through simple things like learning that periods happen, or how to hold a baby. Its vision of joint family may be rose-tinted, but in these divided times it is a pleasure to watch proximity create acceptance, not its opposite.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 30 Oct 2018.