Celebrated Gujarati writer Dhumketu doesn’t get his due in the latest translation of his work

Pic_1609761818026.jpg) |

| Gaurishankar Govardhanram Joshi (1892-1965), who wrote as Dhumketu, was a pioneering short story writer in Gujarati. (Wikipedia) |

“The short story is not the miniature form of the novel... The novel says whatever it wants. The short story, by rousing the imagination and emotions, only alludes to or provides a spark of whatever it wants to say.” These words, in the original Gujarati, appeared in the 1926 introduction to Tankha (Sparks), the first collection of short stories by the Gujarati writer Dhumketu, the nom de plume of Gaurishankar Govardhanram Joshi (1892-1965). Nearly a hundred years later, you can finally read them in English, in Jenny Bhatt's translated volume Ratno Dholi: The Best Stories of Dhumketu.

Bhatt, a Gujarat-born writer and podcaster now based in the US, has clearly thought long and hard about the shape of the book. Taking seriously the burden of responsibility that comes with representing the pioneering Gujarati author to the contemporary English-speaking world, she has picked one story from each of his 24 published collections, plus two of her own favourites. The book certainly displays his range.

It begins with what is perhaps Dhumketu's most anthologised tale, The Post Office, in which a postmaster who once mocked an old man ends up haunted by his ghost. The ending teeters on the edge of the Gothic, making one think of the Russian short story giant, Nikolai Gogol, with its use of the supernatural to invoke a moral justice that social reality rarely seems to grant us. Dhumketu isn't writing ghost stories, but there is often a suggestion that deeply felt hurt or expectation leaves its imprint in the universe even after death—often in the minds of those who caused or ignored it.

Not unexpectedly for a writer born in the 19th century, Dhumketu was also drawn to historical romance as a genre, writing several novels set in the ancient India of the Guptas and Chalukyas. His historical fiction is represented here by Tears of the Soul, which retells the legendary story of Amrapali, a woman condemned by her democratic city state Vaishali to become a nagarvadhu (courtesan, literally “wife of the city”). If such a beauty was to accept any one man as a husband, went male logic, there would be civil war.

Although he turns a critical spotlight onto male-made laws, Dhumketu's real condemnation of Amrapali's predicament is tied to applauding her sacrifice as a mother. In some other stories, too, Dhumketu is revealed as very much a man of his time. Female deservingness is often premised on sexlessness, most sharply in When a Devi Ma Becomes a Woman, the Gorky-inspired tale of a hostel-wali deeply admired by her male hostellers—until it turns out that she is human enough to respond to the odd sexual overture.

Women are also embedded in social hierarchies of caste and class, and suffer their consequences. In The Gold Necklace, Dhumketu reverses the traditional social hierarchy between wife and mistress. Caste appears frequently, as descriptor and motor of plot: the vagharin, whose low social status taints a man who helps her; the gohil and kaamdaar who prop up the colonial-feudal structure of the Gujarati village; Brahminness mentioned by characters to establish their gentility in many stories, including the comical The New Poet.

|

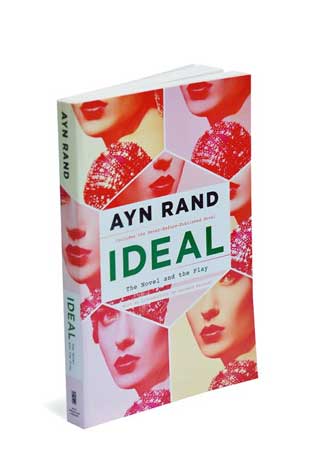

| Ratno Dholi: The Best Stories of Dhumketu, translated from the Gujarati by Jenny Bhatt, published by HarperCollins India, 324 pages, ₹399. |

Dhumketu is no radical, but these stories show an abiding interest in marginalised figures—the penitent criminal in Kailas and The Prisoner of Andaman, the disabled person in Mungo Gungo, the sick low-caste woman Sarju in Unknown Helpers, or the ekla ram, a man who chooses to distance himself from the village's social norms, like Makno Bharthi in The Worst of the Worst.

Some of these solitary souls immerse themselves in art or music: Ratno the dhol-player, the shehnai player of Svarjogi, the sarangi player of My Homes, or even the literary young man of A Happy Delusion. When he writes about these musicians, or even about the aesthetic domesticity of the housewife Kamala in A Memorable Day, Dhumketu is both generous and appreciative.

Fittingly for a writer, perhaps, he displays greater ambivalence when describing literary ambitions. The aspirational poet or writer, especially, gets a drubbing, whether the clerk Bhogilal of Ebb and Flow, the highfalutin train passenger of The New Poet, or the intently focused but talentless Manmohan of A Happy Delusion.

Bhatt's dedication aside, her translations leave much to be desired. Her literal renditions of the original leave us repeatedly in the grip of florid, often archaic language (“Then, because they had not heard such melodious, sweet, alluring, rising and falling music in years, an illicitly joyful passion grew in the soul of thousands” or “Her memory did not endure anywhere now except during the rare occasions of general small talk”), not to mention constantly tripping up against such formations as “slowly-slowly” or “From downstairs, a melodious, bird-like voice came”.

However deliberate Bhatt's approach might be, the English feels jarring; the sentences marred by roundaboutness and redundancy. “What if this amusement was flowing due to his writing?" thinks one character, while a policeman tells a woman “to be careful with [her] tongue when speaking”. Very occasionally one gets a glimpse of what I imagine is Dhumketu's idiomatic Gujarati, such as in Old Custom, New Approach, where a man complains sardonically about modern bureaucracy: “Letters speak with letters. People avoid other people, this is called administration.”

One hopes someday he will receive a better interpreter. In the meanwhile, this is a valuable addition to your Indian classics bookshelf.

Published in Mint Lounge, 5 Jan 2021.