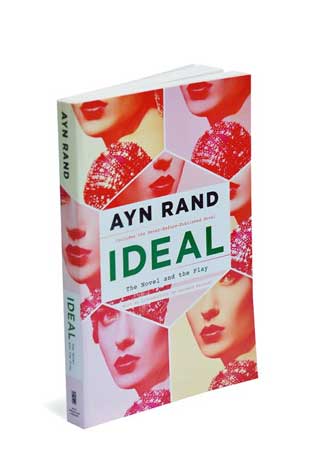

My review of Ideal, by Ayn Rand, in today's Mint Lounge.

This early work, published now, reveals that by the 1930s, she had already arrived at the tenets of objectivism

Ayn Rand was born Alisa Rosenbaum in St Petersburg in 1905, and arrived in the US in 1926. Unlike most Russian immigrants to the US, her change of name was no prosaic shortening or simple Anglicization. Instead of the obvious Alicia or Alice when she dropped Alisa, she took on “Ayn”, from the name of a Finnish writer she had not read. “Rand”, adopted later, was long believed to have come from the Remington Rand typewriter she brought with her but that particular myth of self-creation has been dismantled by two 2009 biographies, by Anne C. Heller and Jennifer Burns.

Rand was nothing if not driven. She spent her first months in the US with relatives in Chicago, and by the time she left for Hollywood midsummer, she had with her her first story in English and four screenplays. One of them was about a “skyscraper hero” who leaps from one building to the next using a parachute.

That story didn’t sell, but Rand did manage to parachute her way into Hollywood. On her first day there, having failed to get a job in the screenwriting department of Cecil B. DeMille studios, she was standing outside when DeMille himself drove by. He gave her a ride, and soon, a job as an extra.

An absolutely remarkable feat which we do not often recognize is that Rand taught herself a new language, not just living and writing in it, but making it the medium of a lifelong ideological project. Her first novel, We The Living, was completed in 1933, but was rejected by a succession of publishers. In late 1934, she had her first commercial success with her play, The Night Of January 16th—a courtroom drama with a twist: The audience got to vote on the verdict. In the fall of 1935, Macmillan Company bought the rights to We The Living. But Ideal was written during the bitter interlude, and Leonard Peikoff, Rand’s designated intellectual heir, suggests in the Introduction that its depiction of “idealistic alienation from the world” is surely connected to “the intensity of Miss Rand’s personal struggle at the time”.

It is interesting then that Rand took as her partial milieu the world of the Hollywood studio, of which she was then a part. Ideal begins with the dramatic disappearance of the ethereal and mysterious film-star Kay Gonda (a kind of Greta Garbo-lite), who then appears in six consecutive stagy episodes, seeking shelter with six ordinary Americans who have written her fan letters that she considers particularly meaningful.

The novel is verbose and theatrical at the best of times, and the play, though crisper, remains a model of pomposity. Considering how early a work Ideal is, what is remarkable is that Rand seems to have already arrived at the principal tenets of objectivism, her stated philosophy. These are often stated thus: The proper moral purpose of one’s life is the pursuit of one’s own happiness, and the only social system consistent with this individualistic morality is laissez-faire capitalism. But this leaves out what seems to me the most disturbing aspect of Rand’s belief system: the filling of the vacuum left by God with an unshakeable faith in heroes—and occasionally heroines. “The motive and purpose of my writing is the projection of an ideal man,” she wrote in a 1963 essay,The Goal Of My Writing.

Ideal, certainly, stands grandly and ridiculously upon this foundation. “I kill the things men live for,” states Kay Gonda. “But they come to see me, because I make them see that they want those things killed. That they want to live for something greater.” That “something greater” seems to have no definition, except for being embodied in the person of Miss Gonda herself. “[I]n you—I have found one last exception, one last spark of that which life is not anymore,” one fan writes to her. “[Y]ou who are that which the world should have been,” gushes another. “None of us ever chooses the bleak, hopeless life he is forced to lead. But in our ability to recognize you and bow to you lies the hope of mankind,” writes the third.

But it isn’t only Gonda’s fictional fans who think she’s an ideal—it is Rand herself. “There is more honour in having killed than in being one worth being killed,” one character says to Gonda, with no one batting an eyelid at this sentiment. And later: “One thousand lives? What are they besides one hour of yours?” The culmination of the novel (and more believably, the play) is an innocent man dying for no reason, only because Gonda lets him. “He wanted to die so that I could live,” she says later.

The idea that there is something ineffably great about a few people, that they are meant to be worshipped by the many, wasn’t exactly original—think of Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas of the death of God, and the Übermensch. What seems pernicious about Rand’s version of heroic individualism is her implication that everyone outside this minority is weak, valueless and hypocritical. And consequently, can be sacrificed.

Published in Mint Lounge, 29 Aug 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment