My Mirror column:

Among 1957’s biggest Hindi hits was Musafir, a triptych of tales about a house and its succession of tenants, which inaugurated the career of Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

"Laakh laakh makaan, aur inmein rehne wale karoron insaan. In karoron insaanon ke sukh-dukh, hansne-rone ke maun-darshak -- yehi makaan (Lakh of houses, and crores of people who live in them. And the mute witnesses to these people's joys and sorrows –these very houses),” runs Balraj Sahni's voiceover as the camera pans across a cityscape, finally settling on one such makaan as the setting of this particular story.

What I just described is the opening sequence of Musafir, a triptych of tales about three different families, connected only by the house they rent in succession. The third film in my series of columns on the top Hindi hits of 1957, Musafir was the tenth highest box office grosser that year, and has several points of interest about it. For one, it was the directorial debut of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, who had come to Bombay from Calcutta with Bimal Roy in 1950. Mukherjee had worked as Roy’s editor at New Theatres for five years, and in making the journey to Bombay at 27, he joined a group of young Bengali men with various kinds of cinematic ambitions. These included the actor Nazir Husain, writer Nabendu Ghosh, assistant director Asit Sen and dialogue writer Pal Mahendra. The second bit of trivia that makes Musafir interesting also relates to a young Bengali man — Mukherjee shares writing credits on the film’s script with the filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak.

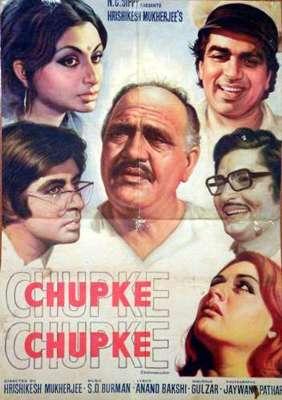

From where we stand now, the raw, powerful Ghatak of Subarnarekha or Titash Ekti Nadir Naam and the warm, gentle Mukherjee of situational comedies like Chupke Chupke may seem to represent two unbridgeable poles of the Indian cinematic universe. But in the late 50s the world was young, the lines between the artistic worlds of Calcutta and Bombay, and those of 'art' and 'entertainment' were still permeable. Thus the man who would become one of the cinematic trinity of grandly ambitious Bangla high art wasn't so distant from the man who would come to stand for the mild-mannered, middle class Hindi comedy of manners. The year after Musafir, 1958, two films released – one was Bimal Roy's marvellous Nehruvian-era ghost story, Madhumati, which was written by Ghatak, and the other was Ghatak's own directorial venture, Ajantrik, in which it is another inanimate object – a car rather than a house – that is at the centre of the human stories Ghatak chooses to tell.

Musafir itself combines Mukherjee's lightness of touch and prodigious talent for characterisation with Ghatak's flair for the melancholy and for the recurring motif. Most of the film unfolds, as was Mukherjee's wont, within the four walls of a house. But Musafir also contains the sense of a streetscape – we view the house first from the chai shop window, and the chatty tea-delivery-boy (Mohan Choti) appears in each narrative. In fact it is he, along with the genially repetitive landlord (David), the gossipy Munni ki Ma, and the friendly neighbourhood drunk Pagla Babu, who stitches the film's three parts into a sociological urban whole.

Like Subodh Mukherjee's Paying Guest, which I wrote about two weeks ago, Mukherjee's first film deals with what was then a relatively new urban world, increasingly unmoored from feudal certitudes. The tenants who are anonymous until they aren't, family units whose legitimacy cannot be vouched for by foreknowledge, village elders or caste networks; nosy neighbours (like Munni ki Ma) who make it their business to establish the traditional 'rightness' of those who have moved into the area. In the first segment here, for instance, Suchitra Sen plays a new bride who yearns to be accepted by her in-laws despite her runaway marriage. The possibility of a nuclear family unit is one she rejects instinctively as inferior to the real thing.

Mukherjee's interest in these new populations, free-floating in space but not quite ready to give up on their connections to community, family, tradition – remained a persistent theme in his films in later years. Tenants, landlords and the negotiation of neighbourhood rules are central to his comedy Biwi Aur Makaaan (1965), and also to the Jaya Bhaduri-Amitabh Bachchan starrer Mili (1975). Both Mili and Bawarchi also begin by visually laying out the neighbourhood, and then using a voiceover to zero in on the one home whose internal dynamics we are to have the privilege of witnessing.

In Musafir, these dynamics seem to involve older men who, despite their 'good' intentions towards their families, are such sticklers for discipline/rules/

From where we stand now, the raw, powerful Ghatak of Subarnarekha or Titash Ekti Nadir Naam and the warm, gentle Mukherjee of situational comedies like Chupke Chupke may seem to represent two unbridgeable poles of the Indian cinematic universe. But in the late 50s the world was young, the lines between the artistic worlds of Calcutta and Bombay, and those of 'art' and 'entertainment' were still permeable. Thus the man who would become one of the cinematic trinity of grandly ambitious Bangla high art wasn't so distant from the man who would come to stand for the mild-mannered, middle class Hindi comedy of manners. The year after Musafir, 1958, two films released – one was Bimal Roy's marvellous Nehruvian-era ghost story, Madhumati, which was written by Ghatak, and the other was Ghatak's own directorial venture, Ajantrik, in which it is another inanimate object – a car rather than a house – that is at the centre of the human stories Ghatak chooses to tell.

Musafir itself combines Mukherjee's lightness of touch and prodigious talent for characterisation with Ghatak's flair for the melancholy and for the recurring motif. Most of the film unfolds, as was Mukherjee's wont, within the four walls of a house. But Musafir also contains the sense of a streetscape – we view the house first from the chai shop window, and the chatty tea-delivery-boy (Mohan Choti) appears in each narrative. In fact it is he, along with the genially repetitive landlord (David), the gossipy Munni ki Ma, and the friendly neighbourhood drunk Pagla Babu, who stitches the film's three parts into a sociological urban whole.

Like Subodh Mukherjee's Paying Guest, which I wrote about two weeks ago, Mukherjee's first film deals with what was then a relatively new urban world, increasingly unmoored from feudal certitudes. The tenants who are anonymous until they aren't, family units whose legitimacy cannot be vouched for by foreknowledge, village elders or caste networks; nosy neighbours (like Munni ki Ma) who make it their business to establish the traditional 'rightness' of those who have moved into the area. In the first segment here, for instance, Suchitra Sen plays a new bride who yearns to be accepted by her in-laws despite her runaway marriage. The possibility of a nuclear family unit is one she rejects instinctively as inferior to the real thing.

Mukherjee's interest in these new populations, free-floating in space but not quite ready to give up on their connections to community, family, tradition – remained a persistent theme in his films in later years. Tenants, landlords and the negotiation of neighbourhood rules are central to his comedy Biwi Aur Makaaan (1965), and also to the Jaya Bhaduri-Amitabh Bachchan starrer Mili (1975). Both Mili and Bawarchi also begin by visually laying out the neighbourhood, and then using a voiceover to zero in on the one home whose internal dynamics we are to have the privilege of witnessing.

In Musafir, these dynamics seem to involve older men who, despite their 'good' intentions towards their families, are such sticklers for discipline/rules/

rationality/tradition that they end up tyrannising wives and daughters, as well as any non-conformist younger men – the young man who marries without parental permission in the first story; the jobless Bhanu (a very youthful Kishore Kumar) in the middle segment, who can't stop playing the fool; or the heart-stopping Dilip Kumar as the violin-playing tragic alcoholic of the last segment (clearly inspired by O'Henry's 'The Last Leaf'). The lawyer brother of Usha Kiron, or Nazir Hussain as the irascible father with money trouble, and Suchitra Sen's father-in-law in the first segment are all men determined to to be merciless, grown-up patriarchs who must be humoured like children – and one can see in their caricaturish excess the roots of Utpal Dutt's character in Golmaal, or Om Prakash's Jijaji in Chupke Chupke.

Musafir has some rough edges, and its tonal shifts from tragic to comic are not always successful. But it is an interesting film, if only for the many ways in which it foreshadows Mukherjee's future filmmaking career.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 20 Aug 2017