An art review, published in Open magazine.

The women whose imaginations currently fill Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art are many things, their work an inventory of artistic possibility.

The ongoing show at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, located, interestingly, in a South Delhi mall, is a tripartite mega-exhibition of the work of several accomplished women artists from India. The first part, ‘A View to Infinity’, is the largest ever retrospective of the works of Nasreen Mohamedi; the second, ‘The Self in Making’, is devoted to the self-portraits of Amrita Sher-Gil; and the third, ‘Seven Contemporaries’, contains work by seven women artists working today.

Collectively named ‘Difficult Loves’ after a collection of short stories by the Italian writer Italo Calvino, the exhibition, in the words of curator Roobina Karode, ‘proposes to talk about adventures, misadventures, complex relationships with objects, subjects, desires and life itself, about trials and errors in the individual artistic journeys of these nine participating artists.’ By bringing together this immensely varied work, the KNMA show makes it impossible for anyone to suggest ever again that the category ‘women artists’ is somehow a self-explanatory one.

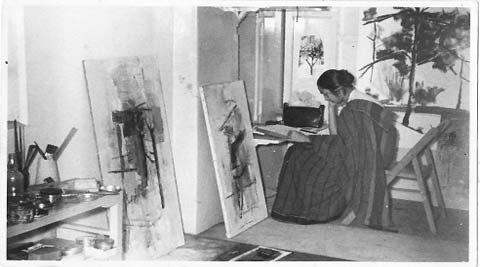

Nasreen Mohamedi died of a rare neurological disorder in 1990 at the age of 53. Over the last decade, she has come to be recognised as one of the most accomplished Indian practitioners of non-figurative art. The KNMA show brings together her delicate drawings, most in ink and graphite, with her black-and-white photographs, which were never exhibited in her lifetime.

Though her early work does have a few figurative images—a woman in a sari, two men sitting—an impulse towards minimalism already exists. The two men, for instance, are drawn in fractured outline—the barest essential strokes needed to describe the form of the human body. Pale washes of colour combined with thin lines hint at trees and houses and electricity wires, or a handcart resting under a tree. Another phase of early work uses repeated brushstrokes a la impressionism to create swatches of colour that suggest—rather than try to recreate—sun and sea and sand. But Mohamedi’s minimalist instincts soon led her in the direction of greater abstraction.

One of her perennial concerns and interests as an artist seems to have been the patterns inherent in nature. Scattered notes from her diary reveal a mind that was often provoked by the effortless beauty of the natural world to question the very purpose of art. ‘To make an effort to do anything seems so futile. Everything in nature is so perfect,’ she writes, and later: ‘I feel so empty and useless. That light on the beach. Those zigzag designs that waves leave on the sands.’

Happily for us, Mohamedi moved on from these feelings of artistic paralysis to producing art that echoed nature. A lot of her work might be thought of as drawing something essential out of the natural and making it visible on paper. Her photographs show how she was drawn to the magic of natural design: the ripples on the surface of the sea and the corresponding ones on sand, the eclipsed moon. Whether in these photographs, or those of manmade creations—the architecture of Fatehpur Sikri, the warp and weft of threads in the weaving of cloth—Mohamedi distils the essence of form.

In another meditation in her diaries, Mohamedi writes, ‘nature disposes itself in rhythm, and only in rhythm is one able to escape time.’ There is in this an echo of another voice—avant garde American filmmaker Maya Deren (1917-61). Deren’s rather strange short film Ritual in Transfigured Time(1946) creates the feeling of watching a dream. This effect of dream time is created through repetition. The rhythmic movement of a woman winding wool, repeated over and over again, produces an alternative to the linear progression of time that film usually seeks to recreate, especially through techniques of continuity editing. Mohamedi’s later art seems to make a similar use of repetition to transcend linearity.

The line remained crucial throughout her work, but her use of it changed drastically. The line ceased to be a way to create a bounded form, to describe a body or a tree. Repeated over and over again, it became something purer, a thing in and of itself. The meshing of lines, their careful placing over each other or at regular distances, creates a sense of depth.

Another aspect of Mohamedi’s relationship with time emerges from another quote on the wall: ‘Waiting is a part of intense living’. This thought seems of a piece with the recreation of her workplace within the museum: the room is dimly lit, except for a low-hanging lamp that illuminates a low white table upon which is placed a blank sheet of paper, a ruler, and a few seashells. From a small music system in the corner comes the magisterial voice of Bhimsen Joshi, to the accompaniment of which Mohamedi apparently often worked late into the night.

Amrita Sher-Gil is among India’s most iconic artists, certainly among the most popularly loved. Her work is starkly opposed to Mohamedi’s in many ways—figurative, rich in colour, keen on symbolism. The most crucial difference seems to be that where Mohamedi turned ever outward, Sher-Gil’s artistic quest, right from her youth, led her inward, shining a light upon her family, her relationships, her connection to India, and, most obviously, herself.

Sher-Gil was born in 1913 in Budapest to a Sikh aristocrat called Umrao Singh Shergil and a Hungarian opera singer called Marie Antoinette Gottesmann. She spent a lot of her childhood in Hungary, then some years in Shimla before going to Paris to train as a painter. In 1934, she was overcome by a longing to return to India, and returned to the country, travelling to see historic centres of Indian art like Ajanta and settling in her father’s family home in Saraya, Gorakhpur.

Sher-Gil’s art is said to have changed in accordance with this geographical shift, from the more European work she did in her early years, to the portraits of rural Indian women she did after 1934, which have been seen as profoundly influenced by Abanindranath and Rabindranath Tagore. While in Saraya, Sher-Gil wrote to a friend: ‘I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque... India belongs only to me.’ But did Amrita belong only to India?

Sher-Gil’s art is said to have changed in accordance with this geographical shift, from the more European work she did in her early years, to the portraits of rural Indian women she did after 1934, which have been seen as profoundly influenced by Abanindranath and Rabindranath Tagore. While in Saraya, Sher-Gil wrote to a friend: ‘I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque... India belongs only to me.’ But did Amrita belong only to India?With its focus on her self-portraits, the show at KNMA offers us a glimpse of the constant, lifelong tussle in which Sher-Gil’s Western and Indian selves were engaged.

In some pencil sketches she did as early as 1927, she appears stocky and dense, her arms and torso chunky. In one of these images, a deliberate curl of hair is placed strategically in the centre of her forehead, calling to mind the Henry Longfellow rhyme: ‘There was a little girl/ Who had a little curl,/ Right in the middle of her forehead./ When she was good,/ She was very good indeed,/ But when she was bad she was horrid.’ Scrawled in dark pencil in the margin of another are the words ‘Prostitutes of the Gods... so-called... Devadasis.’

Placed alongside Sher-Gil’s own images of herself are a series of pictures of her taken between 1927 and 1934 by her father Umrao Singh, himself an immensely talented photographer. In the first, Amrita grins self-consciously out at us, that same curl in the centre of her forehead, deliberately crafted, forced into place. Her attire varies through the series. Dressed in a sari, she sometimes has her head covered or wears a bindi. Elsewhere, she is wearing a long white frock, her hair open.

This desire to experiment with her identity, to perform different versions of the self, emerges just as strongly in her more mature work, best represented by two images from Vivan Sundaram’s digital photo-montage series, ‘Re-take of Amrita’, also at KNMA. Sundaram, Sher-Gil’s nephew, has created several composite frames in which different images of the artist are juxtaposed, accentuating her shifting relationship with East and West.

In one, a photographic Amrita in a collared polka-dotted dress and what looks like a beret—these are the Paris years—sits next to a painted Amrita, in the same pose but now wearing a heavy necklace and a turban on her head, making her look like an ‘Eastern’ figure out of some Delacroix painting. In another, Sundaram overlays Sher-Gil’s Self as Tahitian, in which she posed in the nude in the post-impressionist style of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian women, with a smiling pin-up-style photograph of her in swimming costume.

The work on view under ‘Seven Contemporaries’ seems to revisit some of the concerns of Sher-Gil and Mohamedi. Bharti Kher’s massive triptych is a characteristic agglomeration of bindis—thousands of them stuck onto a black surface in patterns that create the sense of a topographical map. But instead of the dull browns and greens of most maps, here we have a new continent, rich and strange. The brilliant red of bindis evokes blood andsindoor and every aspect of female fertility; the black background appears as rivulets flowing through the mouth of some great river.

Sheela Gowda’s three pieces speak to domesticity and the experience of enclosure. In Margins, dismantled door frames stretch out towards the sky rather than bounding space. In Viewfinder, two window frames with meshes and iron grills press down on the possibilities of seeing. In the disturbing Like a Bird, ropes of hair are strung across a small space. Weighted down with metal forms, they bring to mind the arcs traced by a bird trapped inside a room: now frantic, now weary.

Anita Dube’s Intimations of Mortality (1997) is apt punctuation to all three shows. A concentration of enamelled ceramic eyes stuck to a corner where two walls meet the ceiling, which Dube describes as ‘a feminist insertion inside the neutral interior space of architecture’, it evokes the female body while also producing a vivid, angry reversal of the gaze.

In its exploration of erotic selfhood, it shares something with Sher-Gil, and in its conversation with architectural and natural form—the three planes that meet at the corner of a room, the glossy brittleness of ceramic eyes—it connects with Mohamedi.

It is among the most unsettling things you will see at the show and works somehow to bind together the various styles of the women artists on view at the museum.

‘Difficult Loves’ closed on 30 November, 2013. This piece was published in Open magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment