Today's Mirror column:

Reading in English about Hindi movies: a very brief history of the Indian film magazine as we know it.

Writing about films is one thing; writing about film stars is quite another. There are those who do both with aplomb. But in India, most long-running film magazines have been much more interested in the lives of film celebrities than the content of films.

The first Indian magazine completely devoted to cinema coverage was the Gujarati Mauj Majah, first published in 1924. Among English magazines, Baburao Patel's well-regarded monthly FilmIndia, published from 1935 to 1961, was one of the first. (The legendary and indefatigable Patel, who produced the entire content of the magazine himself – later aided and finally replaced by his wife Sushila – is the subject of a new book called The Patels of FilmIndia, which I'm looking forward to reading).

This was followed by the first trade publications, like KayTee Reports and Tradeguide, concerned not with stars but with predicting the commercial success or failure of particular films. In 1951 came Screen, launched by the Indian Express group in a colour broadsheet format. Screen, because it was concerned both with recent events in the industry and with films under production, could “be situated somewhere between the trade and the fan magazines”, writes film scholar Rachel Dwyer.

Close on Screen's heels came Filmfare, launched by the Times of India group in 1952. Filmfarewas glossy and upmarket, but it intended to be a family magazine and a sophisticated one. The first issue contained a manifesto that stated, “This magazine represents the first serious effort in film journalism in India. It is a movie magazine – with a difference. The difference lies in our realisation that the film as a composite art medium calls for serious study and constructive criticism and appreciation from the industry as also from the public.” This noble intention was cemented by the institution of the Filmfare Awards in 1953. Filmfare remained biweekly until 1988, when financial troubles forced it to become a monthly, which it has been since.

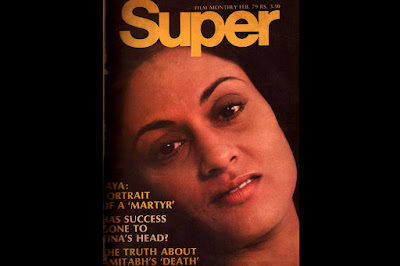

But the big moment of change in English-language film journalism in India was the 1970s, when a clutch of new magazines changed both the way we related to the stars and the language in which we were meant to do it. Jerry Pinto summed up the 70s magazine scene in his superb bitchy-funny Introduction to The Greatest Show on Earth, a spectacular anthology of writing on Hindi cinema that he edited in 2011. “Filmfare was the grand old lady, still published in an improbable size that meant you couldn't open it fully in a crowded bus or train. Stardust was the snazzy newcomer with a hint of middle-class contempt for the arrivistes and outsiders that made up the film industry. Cine Blitz came later and launched itself on the unsuspecting public with Protima Bedi – a Bollywood citizen through her open marriage with Kabir Bedi – running nude on a city beach. In between, for a brief while, there was Super, which had an almost indecipherable column, written as a letter, by Bubbles. Since Bubbles assumed we all knew the stars' nicknames, I often read it wondering at what was really happening and who was doing what to whom. When one did know (Daboo was Randhir Kapoor and Kaka was Rajesh Khanna) one felt validated in one's knowledge.”

Stardust, writes Dwyer, was founded in 1971 by Nari Hira of the Magna Publications group “as a marketing opportunity for his advertising business”. It was meant to be something along the lines of the American celebrity gossip mag Photoplay, more salacious than the then-staid Filmfare. Dwyer's 2001 essay contains the following wonderful account: “Twenty-three year old Shobha Rajadhyaksha (later De), who had been working for Hira for eighteen months as a trainee copywriter, was hired as the first editor. She had no interest in the movie world and had never worked as a journalist, but was hired on the strength of an imaginary interview with Shashi Kapoor, whom she had never met.” The imaginary interview was clearly a thing, combining an opportunity for writerly showing-off with a jokey fantasy that indulged the star's fans. Jerry Pinto cites one ridiculously risqué one with Bindu, from the now-defunct Film Mirror, which ends with the “reporter” waking from a dream. But more of that in another column.

To return to Shobhaa De, she apparently produced the first Stardust issue alone (with one paste-up man). She was later joined by a production staff of three and a team of freelance reporters who “collected stories which she wrote up”: a one-woman show not far from Baburao Patel. But De seems to have stayed put in her office, somewhat unusual for a young journalist. In her memoir Selective Memory: Stories from My Life, De's version of it is: “My eyes and ears were so attuned to reportage that I preferred my colleagues' version of their meetings with the stars to personal encounters.” Dwyer puts it somewhat differently. “De stubbornly refused to move in the film world, only meeting the stars if they came into the office,” she writes, making one envisage a scenario that seems nearly unimaginable today, when a respected and senior film journalist told me that even he finds it difficult to get interview appointments with current stars. Most stars, he added, seem in such a huge rush to finish the interview that it can barely become a conversation.

Super, too, was founded by an exceptionally young team that included Bhavana Somaya and Namita Gokhale. Gokhale, then 20, encountered Dev Anand some four decades later at the Jaipur Literature Festival, and was amazed to have him recall the last time they had met. “It was in 1981, I think,” he mused. “You were with your editor Rauf Ahmed – what was the magazine called...?” Whether it was the fact that these young people were just exceptionally memorable, or that stars in those days met less journalists, I don't know.

No comments:

Post a Comment