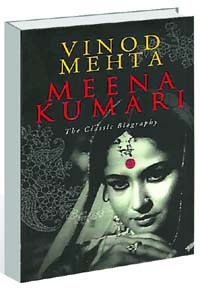

Vinod Mehta's republished biography turns the spotlight back on Meena Kumari.

|

| Meena Kumari in Aarti, 1962. |

Meena Kumari died of liver cirrhosis in March 1972. She was 39. A month or so later, Luis Vaz of Jaico Publishing called a young Bombay copywriter whose self-published book Bombay: A Private View had seen some success. Would he be interested in writing a biography of the woman universally acknowledged as Hindi cinema's greatest tragedienne?

In a memoir published 39 years later, the copywriter described that moment of decision: “Why not, I thought. And with the bravado of a 30-year-old who knew next to nothing about Hindi cinema, I launched into the project.”

That 30-year-old was Vinod Mehta, and the biography he produced in October 1972 was pronounced “the most sympathetic, comprehensive and readable book on Meena Kumari” by the great writer-director KA Abbas. But after that first flush of critical acclaim, the book went out of print. And so it remained for decades, until Mehta's mention of it in his journalistic memoir Lucknow Boy (2011) aroused current-day curiosity.

|

| Meena Kumari: The Classic Biography HarperCollins, Rs. 350 |

Republished by HarperCollins this September, the biography is a remarkable creature. It bears witness not just to the incredibly filmi life of one of India’s most beloved actresses, but also to a past Bombay film world as observed by an outspoken young outsider. Mehta had watched some Hindi films growing up, but he was no starry-eyed fan. Hollywood impressed him more. One of the reasons he took on the project was that he’d read somewhere that Meena Kumari had identified with Marilyn Monroe, and her husband Kamal Amrohi with Arthur Miller.

But what he really wanted was to place in her context the lower middle class Muslim girl who had become, like others of her ilk, a golden goose for her family, and to write about what kind of place India was in the ’70s. “I am often sounding off, and I enjoyed that,” Mehta told Time Out. That youthful pleasure is apparent in the summary dismissals that pepper the book. “For sheer vulgarity, dandyism, shallowness, squalor and dishonesty, the Bombay film world is hard to beat,” (p. 149), or “I can never understand how anyone who has the temerity to call himself an artiste… can find the time and mental apparatus to handle and organise the tortuous deceits necessary for hoarding hot money” (p. 185). “At that time it was fashionable to look down on Bombay cinema, not like now,” Mehta laughed. “And at that age I had an ego the size of a football.” But with zero journalistic experience or connections, it couldn’t have been easy to meet with Hindi film biggies? “Some of them were real prima donnas,” agreed Mehta. “What helped me was I had long hair; I used to wear a white raw silk coat and a tie and I had a bit of a British accent still. These film stars were quite flattered that a London-returned chap had come to see them. I quickly sensed that, and I exploited it.”

Whatever his reservations about the ’70s film world, Mehta has no doubt that it's a much worse place now. “I didn’t find the bitchiness that seems to exist today between [heroines]. There was space for everybody, and respect. Nargis spoke so well of Meena Kumari. And it was all extremely courteous – aap, aap, aap. I didn’t hear a single disparaging remark, not even from Amrohi [her ex-husband],” he said. There were, of course, those who refused to meet him, like her old love Dharmendra, and those, like Gulzar, who gave away nothing even when they did. The legendary lyricist-filmmaker, whom Mehta describes as “a cunning, urbane and sane man”, was bequeathed Meena’s diaries, and back in 1972, he scared Mehta by implying that he was writing a biography of her, too. But no biography ever emerged, and barring a small fraction of her poems, published as Tanha Chaand, Gulzar has kept Meena Kumari’s writing hidden away from the public eye, much to the disappointment of her fans (there are even those who suspect publishing her writing would reveal its influence on his own).

Mehta has no such illusions: he concedes that she may have been a third rate poet, more in love with the idea of poetry than adept at the craft. But, he writes, in a profession where most people “read nothing more taxing than Cine Advance”, that she was “able to put pen to paper… deserves a thirty-one-gun salute.” Mehta’s book is a combination of exuberant excess and judiciousness. He spends a whole chapter on whether she was a uniformly great actress, or only fitfully so. He evokes in loving period detail the stages of her relationship with Amrohi: the famous marathon telephoning, the silly but revealing quarrels over bassi roti, and the more serious ones over who entered Meena's make-up room, which eventually led to the break-up of their marriage. He evaluates her relationships with her family, and concludes that if she was exploited, it was because she chose not to cut herself off from people she felt she needed.

Mehta's recreation of the internal life of the woman he calls “my heroine” may seem rather imaginative to some, but he believes he was a model of restraint. “I didn’t find the nymphomaniac claim to be true,” said Mehta. “But she was quite promiscuous. Younger men, like Dharmendra or Sawan Kumar Tak, attached themselves to her and got breaks. And she almost certainly slept with all the top heroes.” He didn't put that in the book? “But that was standard. Kishore Sharma (married to Meena's sister Madhu) took me to this room with mirrors on the ceiling and said he was servicing her there. But he was such a shady character that I didn’t believe him,” said Mehta. On the other hand, he got fascinating details from her secretary, driver, doctor and three different make-up women: “people who had no axe to grind”.

The book has brought offers to write about other film stars. “But present-day stars will accept only hagiography. Their PR people will give you a crore or two, but they want to vet your manuscript,” Mehta said. In any case, he hasn’t seen a complete Hindi film for 30 years. “These films of globalised youth, I find them completely artificial. I don't find becoming a famous rock star very interesting. Maybe I'm just too old.”

Published in Time Out Delhi, Oct 2013.

1 comment:

Great Read.. Totally captivating.. A person's life captured so real.. Go for it..

Kisi ka pyaar leke tum ...

Naya jahan basaoge.....

Yeh shaam jab bhi aayegi ..

Tum humko yaad aagoge....

Ajeeb Daastan hai yeh...

Post a Comment