An essay published in Tehelka magazine in November 2009.

The figure of the tawaif continues to haunt popular culture, but what sent the real ones into obscurity?

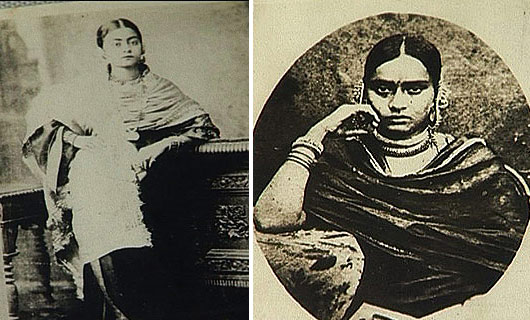

From Umrao Jaan to Pakeezah to Chandramukhi, the figure of the tawaif has been a figure of fascination in the popular South Asian imagination: the bejewelled, sensuous dancing girl with a golden voice – and almost always, a golden heart. To our Hindi-film-overloaded eyes, therefore, it may seem strange for an instant to look upon the black and white images of women who populate The Other Song, Saba Dewan’s film about tawaifs, looking out of the frame at us with a gravitas we do not expect.

But the gravitas is ephemeral. In one revealing moment, the camera pans an old album, with the moving finger on screen stopping at a pleasantly plump face. The grainy voice of an old sarangi player says, “Yeh Rasoolan Bai hain.” The filmmaker asks, “Kya yeh hamesha itne saade kapde pehentin thi? (Did she always wear such plain clothes?)” The reply is brusque and quietly ironic: “Mujra naach toh karna nahi tha. (Well, she wasn’t going to dance the mujra.)”

Rasoolan Bai gave up the mujra – the expressive, sometimes suggestive kathak-based dance that accompanied the tawaif ’s music – in 1948. At the same time that she moved out of her kotha and into a gali ka makaan in Banaras, the woman whose aching songs were perhaps India’s most famous renditions of the thumri stopped performing in her own city. The timing is remarkable. As India and Pakistan entered independent nationhood, the thumri was taken out of the kotha. A musical genre whose very form — intimate, expressive, always sung in a first-person female voice — had emerged from the courtesan’s salon, had, in order to survive in the bright light of modernity, to move into the concert hall, the radio station, the cinema. And in order to be heard in this new world, the tawaif herself had to become a ganewali or – in even more Sanskritised form – a gayika.

The most famous of such successful metamorphoses is that of Akhtari Bai Faizabadi into Begum Akhtar. The courtesan who had achieved fame in her teens became a respectably married lady, even giving up her singing career for years, “only to emerge into the public domain transformed into a national symbol iconic of the courtly musical culture which had shaped her,” writes scholar Regula Qureshi. But the nation exacted its toll. In order to be the voice of a new India, Akhtari Bai had to live a double life – her newfound respectable status was dependent on dissociating herself from every shred of her past, while the power she had over her audience, what independent scholar and historian Saleem Kidwai calls “chemistry”, derived in large measure from that very past.

Saba Dewan’s fascinating film, The Other Song, derives its name from a similar instance of doubling, of a repressed erotic self. Told by a respected Banarasi musician called Shivkumar Shastri that Rasoolan Bai had once recorded a different version of her famous Bhairavi thumri “Lagat karejwa mein chot (My heart is wounded)”, Dewan set out in search of the lesser-known variation. As she asks musician after musician (and later, tawaif after tawaif) if they’ve ever heard the version that goes, “Lagat jobanwa mein chot (My breasts are wounded)”, without success, we begin to see glimpses of a hidden world, a world whose frank sexuality and often joyful bawdiness were pushed deep below the surface, often by its own practitioners. Song after song turns out to have had its lyrics altered to suit ‘respectable’ tastes – from soibe (sleep) to jaibe (go), choli (blouse) to odhni (veil).

The tawaifs of North India (like South India’s devadasis) came from hereditary performing communities. According to historian Katherine Butler Brown, the term tawaif was first used to describe communities of female singers and dancers in Dargah Quli Khan’s Muraqqa’-i-Dehli (1739-41). But it was not until the early 19th century that it became a catch-all term. Even then, Brown argues, before 1857 there was always a distinction made “between elite tawaifs who were highly cultured, highly refined, models of etiquette and masters of performance genres, who might only have had a single sexual patron in their lifetime; and tawaifs who were less talented, less well trained, and thus more dependent on sex work”

BUT AFTER 1857, when British Crown Law came into effect throughout India, all tawaifs were criminalised alongside common prostitutes, with court judgements stating that singing and dancing were ‘vestigial’ activities while their real income came from prostitution. Meanwhile, the rising middle class, “influenced by Victorian values and empowered by colonial law, increasingly dismissed the tawaif as immoral and decadent, and began various moves to ‘rescue’ Hindustani music from them,” says Brown. The campaign for a national music — cleansed of its associations with tawaifs and Muslim musicians — aimed to make it appropriate for middle class women. In a stunning double move, the very processes that enabled ‘respectable’ women to come out of purdah worked to invisibilise the highly skilled, often highly educated, women who had been ‘in public’ all along: the tawaif.

With the decline of the feudal patronage that had sustained the kotha and its arts, many tawaifs explored other options. All India Radio (AIR) in its early days was almost entirely dependent on the ganewalis, as were recording companies: it was tawaifs like Gauhar Jan who were the first gramophone superstars. But in the early 2000s, a skilled singer like Saira Begum (one of the women from tawaif backgrounds that Dewan shot with) gets a recording slot at AIR in Banaras because of a zealous Italian pupil, only to be humiliated with a ‘musical theory’ examination she cannot possibly pass.

As the new guardians of music locked it up and shut the door, women from tawaif backgrounds entered first the theatre company, and later, the movies. “Cinema becomes a part of tawaif history, documenting tawaifi arts we’d never get to see – and also providing a way for the tawaif to reinvent herself,” says Kidwai. “And this reinvention was both on screen and off it. If Hema Malini in Sharafat wears plumes and a tiara to do a mujra, one can’t complain of inauthenticity: many real tawaifs like Siddheshwari learnt to sing in English – even if it was Twinkle Twinkle Little Star!” The tawaif’s remaking of self, as Kidwai points out, could take more radical forms: such as in the case of Nargis, whose mother Jaddan Bai prepared her for a cinematic career by teaching her everything except how to sing. The stardom of Nargis – the ganewali’s daughter divorced from the gana – demonstrated one route by which the tawaif could make it in the modern world. (It is tempting to conclude that this was the necessary obverse of the rise of the playback singer – the disembodied female voice who retained respectability by never being seen on screen.)

As the new guardians of music locked it up and shut the door, women from tawaif backgrounds entered first the theatre company, and later, the movies. “Cinema becomes a part of tawaif history, documenting tawaifi arts we’d never get to see – and also providing a way for the tawaif to reinvent herself,” says Kidwai. “And this reinvention was both on screen and off it. If Hema Malini in Sharafat wears plumes and a tiara to do a mujra, one can’t complain of inauthenticity: many real tawaifs like Siddheshwari learnt to sing in English – even if it was Twinkle Twinkle Little Star!” The tawaif’s remaking of self, as Kidwai points out, could take more radical forms: such as in the case of Nargis, whose mother Jaddan Bai prepared her for a cinematic career by teaching her everything except how to sing. The stardom of Nargis – the ganewali’s daughter divorced from the gana – demonstrated one route by which the tawaif could make it in the modern world. (It is tempting to conclude that this was the necessary obverse of the rise of the playback singer – the disembodied female voice who retained respectability by never being seen on screen.) Cinema, though, isn’t an accessible career for most women. The two other films in Saba Dewan’s trilogy address more subterranean worlds of female performance. Delhi-Mumbai-Delhi (D-M-D) centres on Riya, who dances in a bar in Mumbai but is from Delhi, while Naach is about girls who dance to Bollywood numbers on massive, rickety stages in the town of Sonpur, between Muzaffarpur and Patna, during the annual cattle fair. For Dewan, the differences between these categories of women outweigh any similarities. Her D-M-D protagonist Riya, from an ordinary working class background, may have gained confidence and decision-making power within her family, but she remains wage labour. “The tawaif was much more her own mistress: the owner of the space, the person who paid the accompanists,” says Dewan.

Whether we like it or not, though, the tawaif remains the imagined reference point. “There is an attempt to recreate the mujra past, mediated via Hindi films,” acknowledges Dewan. “In Bombay bars, the girls wear so-called Indian costume – ghaghra choli, partly because it’s easier to get license for ‘Indian dance’, but also because it fits the audience’s appetite. The man there wants to imagine Rekha dancing for him, at least.” Even the filmic bar dancer draws on the pure tawaif of the 1970s Hindi movie: Tabu in Chandni Bar must remain chaste while working in a bar, just like Asha Parekh in the kotha of Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki.

But the relationship between bar dancers and tawaifs runs deeper. Ethnomusicologist Anna Morcom estimates that 80-90 percent of Mumbai bar dancers, “by informal accounts”, are hereditary professional performers from tribes like the Deredar, Nat, Bedia and Kanjar. They have also been the target of a moral campaign eerily similar to the Anti-Nautch campaigns of a century ago. In 2005, a ban on dancing in Mumbai bars made 75,000 such women redundant. It is still in force.

In early 20th century India, it was dance that seemed to lie at the root of moral opprobrium. The tawaif gave up the mujra to acquire respectability as a concert singer or actress. But in a newly-globalised India where ‘Bollywood dance’ is now a legitimitised ‘cool’ activity for the urban middle classes – think NRI/urban weddings, Shiamak Davar classes, TV shows like Boogie Woogie and Nach Baliye, feeding back into films like Dilli-6 or Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi – how does dance re-acquire its immoral connotations when performed by women in bars? That is a new double standard that will take longer to resolve.

From Tehelka Magazine, Vol 6, Issue 44, Dated November 07, 2009