My Mirror column:

The jungle still sustains millions in India. What does indie

cinema make of the conflict that takes place when modernity vies for their

minds and hearts?

|

| Radhika Apte and Girish Kulkarni in the fine short film The Kill (2016), dir. Anay Tarnekar |

I have spent the last week in a village near Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh. Living with a local Gond family in a rural homestay that abuts the forest, I've had some occasion to contemplate not just the differences between city and village, but between village and jungle. The human move from hunting and gathering to cultivation, ie, from the nomadic life to the settled, agricultural one, is usually seen as an advancement for the species, and urban life is perceived as a step up from the rural. In this view of the world, the index of human development is the extent of our conquest of nature.

The idea that human beings could live in sync with the natural world, could choose to depend on the wilderness, seems either romantic or revolutionary. Of course, you might say that the key word here is 'choose' -- when humans are forced to live at nature's mercy, it can often mean fear and suffering.

That sense of

mystery and majesty is what still makes the forest such a powerful place. For

thousands who live on the forest's edge, or in tiny parcels of land carved out

of the wilderness through the labour of generations, the jungle can simultaneously be worthy of worship –

and something they are trying to separate themselves from. Being 'jungli' has

never been respectable in the eyes of mainstream society, but most such

communities' lives are still tied to the forest, not just economically but

culturally as well.

Given how strong the jungle's hold is over large numbers of Indians, IT has featured rather minimally in our cinema. Pradip Krishen's under-watched Electric Moon (1992), written in collaboration with Krishen's then-partner Arundhati Roy, took a swipe at the entire Indian wildlife set-up. Set in a fictitious Indian national park, it featured a family of Anglicised ex-royals who successfully sell foreign tourists a package of Oriental tradition and ferocious wildlife, both half-fiction.

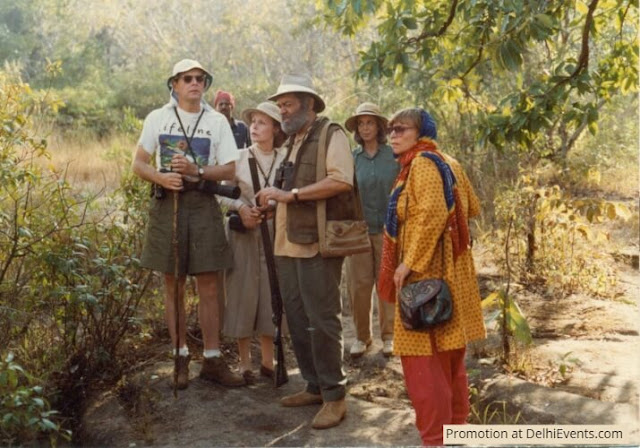

|

| A still from Pradip Krishen's acerbic comedy Electric Moon (1992), set in a wildlife resort |

The next Indian indie I can recall that was set in a wildlife reserve is Ashvin Kumar's stilted 2009 feature The Forest. Despite its grave flaws, I mention it here because it unconsciously mirrors modern urban civilisation's deeply-conflicted relationship with the jungle. An urban couple (Nandana Dev Sen and Ankur Vikal) arrive in a jungle for some quality time, only to encounter the wife's belligerent ex-boyfriend (Javed Jaffery, playing a cop) -- and a vengeful, man-eating leopard. Kumar's direction hinges on portraying the jungle as a place of menace: Spiders preying on insects, haunted temples, a weird saadhvi, and a leopard that really has it in for humans. But this jungli B-grade horror movie comes with a 'Save the Leopard' postscript: The leopard in question turned maneater when injured by a poacher.

I didn't mind Kumar's idea of the jungle as bringing out the city men's masculine competitiveness, testing their testosterone, as it were. “We can go out tonight, if you want, hunting-shunting, yaar,” proposes Jaffery to his ex-rival Vikal. “Centuries of instinct right here, in your balls.” More interesting is Vikal's opening voiceover, suggesting something supernatural about the forest: “I have come to believe we were summoned. That we answered some primeval call. And that nothing that happened that night was either chance or coincidence.”

Kumar's film doesn't deliver on that promise of enchantment. But entering the jungle can often suspend one's sense of modern-day reality, a feeling most clearly embodied in animals whose raw physical presence can still reduce human beings to our most elemental fears. Anay Tarnekar's taut short fiction, The Kill (2016) captures it spectacularly.

Currently available on a streaming platform for curated arthouse and classic cinema, The Kill casts the adept Marathi actor Girish Kulkarni as a poor adivasi man called Gopal who spends his nights gambling away his wife's meagre earnings -- and his days following a tiger. Tarnekar successfully captures not just the feel of the jungle and the great beast's leisurely, loping gait, but the grave, hushed awe with which Gopal treats him. And yet there is also an intimacy there. “Balasaheb,” scoffs his wife (Radhika Apte), referring to her husband's name for the tiger. “What is he, your uncle?” But a statue of a tiger finds place in the family shrine.

The film does not mention it, but the tiger (and sometimes also the leopard) has long been revered as a deity by communities that share a landscape with it. The people of the Sunderbans, the mangrove-covered islands that are home to the largest population of tigers in South Asia, believe in a greedy, man-eating deity called Dokkhin Rai, who is half-Brahmin sage, half tiger-demon. In the North East, the Garos wear a necklace of tiger claws for protection, while the Mishmis see the tiger as their brother. In the forests of western India (where Tarnekar's film is set), the tiger is worshipped by many adivasi communities under the name Waghoba or Waghjai or Wagheshwar, with many beliefs and rituals believed to protect both humans and their livestock. In the Gond home from which I write this column, the domestic shrine has no tiger god – but the man of the house, an ex-forest guard, keeps the tiger as a totem on his motorbike.

But as modernity beckons, it often asks people to sacrifice their old gods. Tarnekar's film ends in tragedy. The death of one's gods is a kind of death, too.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 7 Mar 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment