Late to put this piece I wrote for Firstpost up on the blog, this year's online edition of DIFF is over. But these five films are totally worth looking out for.

|

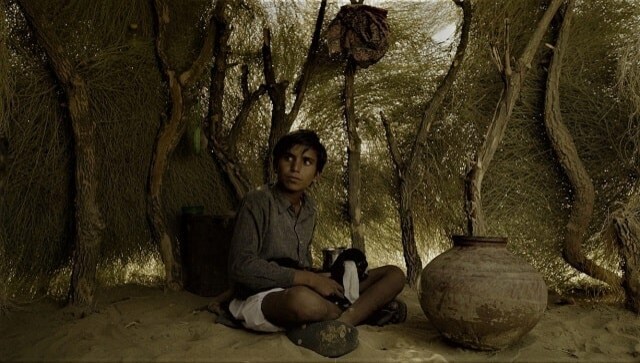

| Still from Pushpendra Singh's wonderful film Pearl of the Desert, 2019, about a Manganiar boy musician called Moti |

The Dharamshala International Film Festival went online this year, making its thoughtfully curated mix of features, documentaries and short films available to anyone in India with a screen and an internet connection, offering both season tickets and a daily Binge pass. Sunday, 8 November, is the last day of this year's festival. I've picked out five unusual films worth the price of admission:

Pearl of the Desert, 2019

Documentary | Rajasthani | 1 hour 22 mins

A boy is walking home with a group of other boys, all wearing that familiar dull blue shirt that is the uniform of countless government schools across India. Suddenly he falls behind, telling the rest to go ahead. “You do this every day!” complains another boy in the group. But they carry on, and the boy settles himself on a crooked tree trunk and begins to sing. As the rich, rugged notes emerge from his throat, the desert seems to spring to life. In case the sound doesn't thrill you, the filmmaker catches a black buck leaping up at the sound of Moti's voice. Then another. Animals seem to respond to the beauty of Moti's music, evoking mythical depictions of cattle gathering to listen to the flute-playing Krishna.

It is the sort of coded, powerfully cinematic image that makes Pushpendra Singh's hybrid documentary on the Manganiars such a layered, resonant piece of filmmaking. Time and again the film reminds us, without a word, that we live in a country of remarkable admixture: a country in which Muslim musicians have for centuries been the appointed bards to the upper caste Hindus of the Thar Desert.

It is something to listen to these men singing the praises of their Hindu patrons: enumerating the heroic exploits of their ancestors, laying out their genealogies, mourning the departure of their daughters — all in words profoundly redolent of the desert. If one song describes the carriage of the camel, another pays tribute to the dusky beauty of the lover in the courtyard, while one particularly stunning verse asks the stubborn lover to come back home, saying, “I have written you a carnival, at least now return”.

Whether the occasion is a birth or a marriage or any other celebration, the Manganiars are always called upon. They sing songs to the goddesses their patrons worship, and they also sing songs to the pirs of the Thar desert. The film closes with a group of Manganiar men harvesting cluster beans, singing in joyful unison a song that invokes Allah. In one of the film's reenacted scenes, Moti's grandfather is asked to relate the community's history — he connects them with Parashuram, with stories about asking for necklaces (maangan, haar), and their name to the Sanskrit word “mangal”, meaning auspicious.

Whenever the increasingly misguided votaries of Hinduism insist that their vengeful politics of purity is the only defense of Indian tradition, it is worthwhile bringing up the Manganiars — for this, too, is our tradition. One we must now fight to keep alive.

|

| Still from the delightful Gaza Mon Amour, 2020 |

Gaza Mon Amour, 2020

Fiction Feature | Arabic | 1 hour 27 mins

Set in the small, densely populated Palestinian territory of Gaza, this film about an ageing fisherman who decides he has had enough of singledom is a quiet delight just for the stellar performances by Salim Daw as the externally crotchety but secretly romantic Issa and Hiam Abbas as the serious-faced widowed seamstress whom Issa finally gathers the courage to court after a naked ancient statue lands in his fishing net — that feels like a sign. Atmospherics are provided by the rundown location, where checkpoints, power cuts and bombings are the norm — as is the fact that many of the younger people want to escape to Europe even via the dangerous illegal route. Directed by Tarzan Nasser and Arab Nasser, this gently comic romance comes to DIFF after a premiere at this year's Venice Film Festival and the NETPAC award for best Asian film at Toronto.

|

| Still from the documentary Influence, 2020, a film about the dangerous directions in which advertising and PR have taken us |

Influence, 2020

Documentary | English | 1 hour 45 mins

Tim Bell was a British advertising man who went from being part of the founding team of Saatchi & Saatchi to Margaret Thatcher's campaign manager, his “Labour's Not Working” hoardings held responsible, among other things, for the decimation of the British Labour Party in that election. Diana Neille and Richard Polak's ambitious documentary portrait of Bell unpacks the rise and fall of a morally dubious man who created and ran the world's most influential political consultancy for decades. Bell Pottinger's clients ranged from the Chilean dictator Pinochet to South African Presidents FW De Klerk and Jacob Zuma. He was hired by the Pentagon to create a flood of propaganda videos in post-Saddam Iraq and by the Gupta Brothers to stir up racial violence in South Africa using hired bots to tweet and post on #whitemonopolycapital.

The film's watchability is aided by its incorporation of an interview with an aged Bell, who died in the summer of 2019 — perhaps precisely because Bell gives away so little, even as he has supposedly decided to tell his story. But its true impact lies in using Bell's life to trace the transformation that characterises our era perhaps more than any other: the dangerous transformation of advertising and marketing from an “art form into a science — and in many respects, into a workable weapon”. Those words belong to Nigel Oakes, an ex-Saatchi & Saatchi man now infamous as the founder of the SCL group, the parent company for Cambridge Analytica. The untrammelled rise of “strategic communication”, alongside social media, is the story of our times, altering political outcomes across the globe for several decades, and now scarily part of our present in India. In Oakes' words, what was once “just democracy” is now a “controlled democracy, maybe available to the highest bidder.”

|

| Still from the gripping Yalda, 2019: Iranian realities filtered through the drama of a reality TV show |

Yalda, 2019

Fiction Feature | Farsi | 1 hour 39 mins

Winner of the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize (Dramatic) at the Sundance Film Festival this February, Massoud Bakhshi's film Yalda, A Night for Forgiveness is a gripping drama that manages to reveal a great deal about the contradictions and hypocrisies of present-day Iran. The film unfolds on the set of a TV show called 'Joy of Forgiveness', during which a woman convicted for killing her husband might receive a pardon from her husband's daughter — and thus be saved from the death penalty.

Bakhshi based his fictitious show on a real show called Mah-e-Asal that aired daily on Iranian television during the month of Ramadan from 2007 to 2018, and does wonders by alternating between the scripted reality we see on TV and the real drama taking place off-camera. The story of why the 20-something Maryam Komijani married her late father's 65-year-old employer and became pregnant with his child brings into view not how skewed Iranian law is against women — the permissibility of 'temporary marriage', the greater claims of sons over family property — but also the deep fault lines of class in Iranian society. Dominant social morality and the law may see Maryam a certain way, but it is hard to look away from the alternative picture the film shows us.

Ghar Ka Pata, 2020

Documentary | Hindi, Kashmiri, English | 1 hour 7 mins

The filmmaker's search for the home she left at six is the basis of a personal essay about a very political place. Madhulika Jalali's family home was a traditional house in the neighbourhood of Rainawari in Srinagar, among the areas in the city that was home to the Kashmiri Pandit community. Like thousands of other Pandit families, Jalali's Hindu parents found themselves forced to leave the valley by the events of the early 1990s, when militancy in Kashmir took a dangerously communal turn. Like the others, they were never to return. The film makes this tragic political-communal context visible through a very personal keyhole. As if to compensate for her own lack of memory, Jalali tries to find an image of the house she can't see in her mind. When her own family albums are exhausted, the search leads her to cousins and relatives — and eventually to Srinagar.

|

| Poster for Madhulika Jalali's moving personal documentary Ghar Ka Pata, 2020 |

The film splices these journeys with Jalali's two elder sisters reminiscing, about the house but also about the traumatic nights leading up to their departure, when proclamations of violence made from the neighbourhood mosques made their father dig out his hunting rifle — but eventually take his close Muslim friend's advice to leave.

Her parents, like most adults Jalali speaks to, remain reticent. But those who were younger then, seem happy to speak. Jalai's sisters talk about how happy and peaceful their childhoods had been in the Srinagar of the1980s: the fruit trees in their garden, the snow they used to try to make into ice cream, the neighbourhood shop from which they bought dahi, the walking route they'd try to take home to get their hands on any festive meetha chaawal being distributed. But even within this gently nostalgic past, one can see the inevitable seeds of the future. In one remarkable anecdote, one of the sisters recalls how in those months that Doordarshan telecast Ramanand Sagar's version of the Ramayana, Hindu and Muslim children alike used to come out onto the streets of their neighbourhood with homemade bows and arrows, taking aim with a "Jai Shree Ram".

Jalali doesn't dwell on it, or on anything really. Her film has a lightness that sometimes feels surprising. Is sorrow filtered through time and distance and forgetting still sorrow? Perhaps the answer is, sometimes.

Published on Firstpost, 8 Nov 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment