My Mirror column:

Continuing my short history of the Indian film magazine in English: editor Burjor K Karanjia and his many publications.

Continuing my short history of the Indian film magazine in English: editor Burjor K Karanjia and his many publications.

In last week's column ("Stars,

Scandals and Fandom", Jun 21, 2015), I began a short history of

the English-language Hindi film magazine. Starting in the 1930s, I

brought the story down to the 1970s, when a series of new magazines

altered the tone and texture of Indian film journalism in English.

But in 1970, the highest-circulating

English magazine about Hindi cinema was Filmfare. It was edited

by the late Burjor K Karanjia, whose politeness, erudition and

general gentlemanliness were legendary. Karanjia was an unlikely film

journalist: a Parsi from Quetta, Karanjia qualified for the

much-prized Indian Civil Service in 1943, but got quickly bored and

decided to abandon a potential bureaucratic career to explore other

options.

In his memoir, Counting My

Blessings (Penguin, 2005), he describes how his fascination with

cinema, first kindled in his Wilson College years by a chance

witnessing of Franz Osten directing the lovely Devika Rani on the

sets of his film Always Tell Your Wife, grew into a serious

interest in film journalism. Being from a moneyed family, the

27-year-old Burjor decided to enter the field by launching a

magazine. (Burjor's brother Russi Karanjia had already founded the

investigative news tabloid Blitz, to which Anurag Kashyap's Bombay

Velvet recently paid fictional homage.)

Cinevoice, launched on June 7, 1947 at

the Taj Mahal Hotel, in a glittering ceremony attended by many film

grandees, was meant to "represent the industry's point of view"

and fight its battles, while also being, in Karanjia's own words, "a

journal that was clean, that was constructive and that had a

conscience". Among the 'battles' waged in the pages

of Cinevoice was a campaign "to plead for social

recognition of the film community". It may seem difficult to

imagine in our Bollywood-besotted era, but in those days, writes

Karanjia, "film stars found it difficult to secure flats in

decent localities in the city. No club, moreover, would admit film

stars as members." Motilal, and later David Abraham, were the

first actors to be admitted to the Cricket Club of

India. Cinevoice also tried to gain film folk

respectability by marshalling them into national political

participation. He credits his colleague Ram Aurangabadkar with the

idea of getting three contemporary actresses -- Nargis, Snehprabha

Pradhan and Veera -- to attend the first All India Congress Committee

(AICC) session held after Independence, and report on it

for Cinevoice.

Karanjia is also credited with

instituting a system of film awards as early as 1949 - the Cinevoice

Indian Motion Picture Awards (CIMPA) - and for programming a live

charity show to raise money for "Kashmir Relief and Troop

Comforts", called "A Nite with the Stars." Neither of

these ventures quite took off independently, but both live shows with

the stars, and film awards (which Karanjia managed to run with

greater success as Filmfare editor), have proliferated to

such a degree that our cinematic culture is unimaginable without

either. Cinevoice did not last long, and neither did

Karanjia's other self-funded journalistic venture, Movie Times.

But with the editorship of Filmfare

came a certain stability. The magazine was a commercial publication

that gladly put Hema Malini or Rajesh Khanna or a bikini-clad

Sharmila Tagore on the cover, but also allowed Karanjia the space to

do what he had set out to in Cinevoice: represent the voice of the

film industry.

In the February 13, 1970 issue, while

applauding the liberal attitude taken towards film censorship by the

Khosla Committee Report, Karanjia's editorial called it out for

equating commercial considerations with dishonesty, and wrote that

the charge "betrays an ignorance of the many complex factors

that have made film-making in India an adventure and a gamble, and

that have attracted to it the wrong type of finance and the wrong

type of filmmaker."

Karanjia also combined in his person

roles that today might seem impossibly divergent: he edited Filmfare

for 18 years (and Screen for ten), while being Chairman of the Film

Finance Corporation (FFC, later to become NFDC). The same February

13, 1970 issue of Filmfare, for instance, reported a press conference

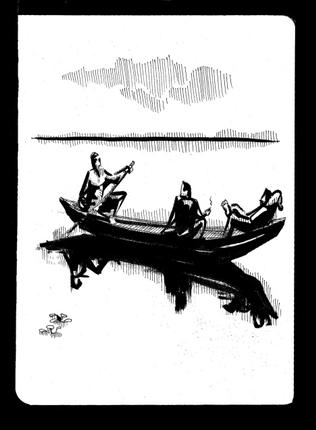

at which film director Basu Chatterjee discussed the film he had just

finished shooting, with a loan from the FFC: Sara Akash. Chatterjee,

the report noted, was a well-known Blitz cartoonist who had

adapted Rajendra Yadav's Hindi novel into a film with an all-new cast

and "a determination to steer away from songs, dances and other

cliches of the Hindi cinema".

The magazine quoted its own editor as

having stated at the press conference that "Audiences, I think,

are ready... The question no longer should be where these films will

be screened, but what sort of films should now be made." The

report went on: "The Corporation, he revealed, has already sent

a proposal to the government for securing a network of theatres based

not on opulence, but utility."

As editor, he was credited with almost

doubling Filmfare's circulation, and making a genuine effort to

return the Filmfare Awards to their early prestige. He went on to

write even sharper editorials for Screen.

Karanjia resigned from his position as

FFC Chairman during VC Shukla's unsavoury reign as Minister for

Information and Broadcasting during the Emergency, in January 1976

(though he did later become NFDC Chairman). But what distinguished

BKK was a rare combination of traits: an enthusiasm for helping

finance a new kind of cinema, but never being disdainful of commerce.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 29 Jun 2015.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 29 Jun 2015.